One of the New Brunswick Museum’s major annual events, the 7th annual NBM BiotaNB, has drawn to a close. Every year, researchers from across Canada and the United States join NBM scientists in one of New Brunswick’s 10 largest Protected Natural Areas (PNAs) to study the area’s biodiversity for a two-week period. BiotaNB targets each PNA for two years in a row: the first year’s event takes place in early summer and the second year’s event takes place in mid-August.

This was the NBM’s first year braving the mosquitoes and adventurous terrain in the Nepisiguit PNA and among the researchers’ many interesting discoveries was a variety of mushrooms.

Above, Amanda Bremner, Curatorial Assistant for Botany and Mycology, holds a collection of Amanita muscaria var. guessowii. This specimen was found in Mount Carleton Provincial Park, near Nepisiguit PNA. The genus Amanita includes some of the more beautiful and charismatic mushrooms in the world, as well as delicious edibles (like Amanita jacksonii) and deadly poisonous ones (like Amanita amerivirosa and related species, commonly known as “Destroying Angels”). A good reminder that being able to properly identify mushrooms is always needed when foraging them for food.

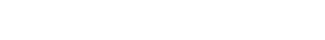

Finding mushrooms in the field is one thing: it’s a whole other challenge to determine a mushroom’s species. Pictured above is a mushroom belonging to the family Psathyrellaceae, which includes many species of “inky cap” mushrooms in the genera Coprinellus, Coprinopsis and Parasola. To help determine the genus and species, part of the mushroom cap was placed on a slide in hopes that it will leave a spore print on the glass. This inky cap has left an excellent print, meaning that the spores are mature: they can be measured to help determine the species of the mushroom. The colour of the spores can also be used to help identify the species. This makes one realise how a single find can take up hours of a researcher’s day to examine.

Spore prints can also be made at home on paper. Because one can’t know whether a spore print will be dark or light, put half of a mushroom cap on white paper and the other half on black construction paper so that at least one side of the spore print will be visible. Keep the mushroom on paper in a cool, covered place overnight (eg. in a plastic container in the shade) and you should have a spore print in the morning.

Amanda has a number of other tricks up her sleeve to help determine a mushroom’s species. Above is a mushroom of the genus Russula. This specimen has a sticky cap, which helps narrow down the possibilities of its species.

The colour of the cap can also be a helpful clue. Because different people might use various words to describe the same colour, Amanda compared the colour of the mushroom cap against the colours in a book to ensure that her description of the colour is the same as other researchers would use.

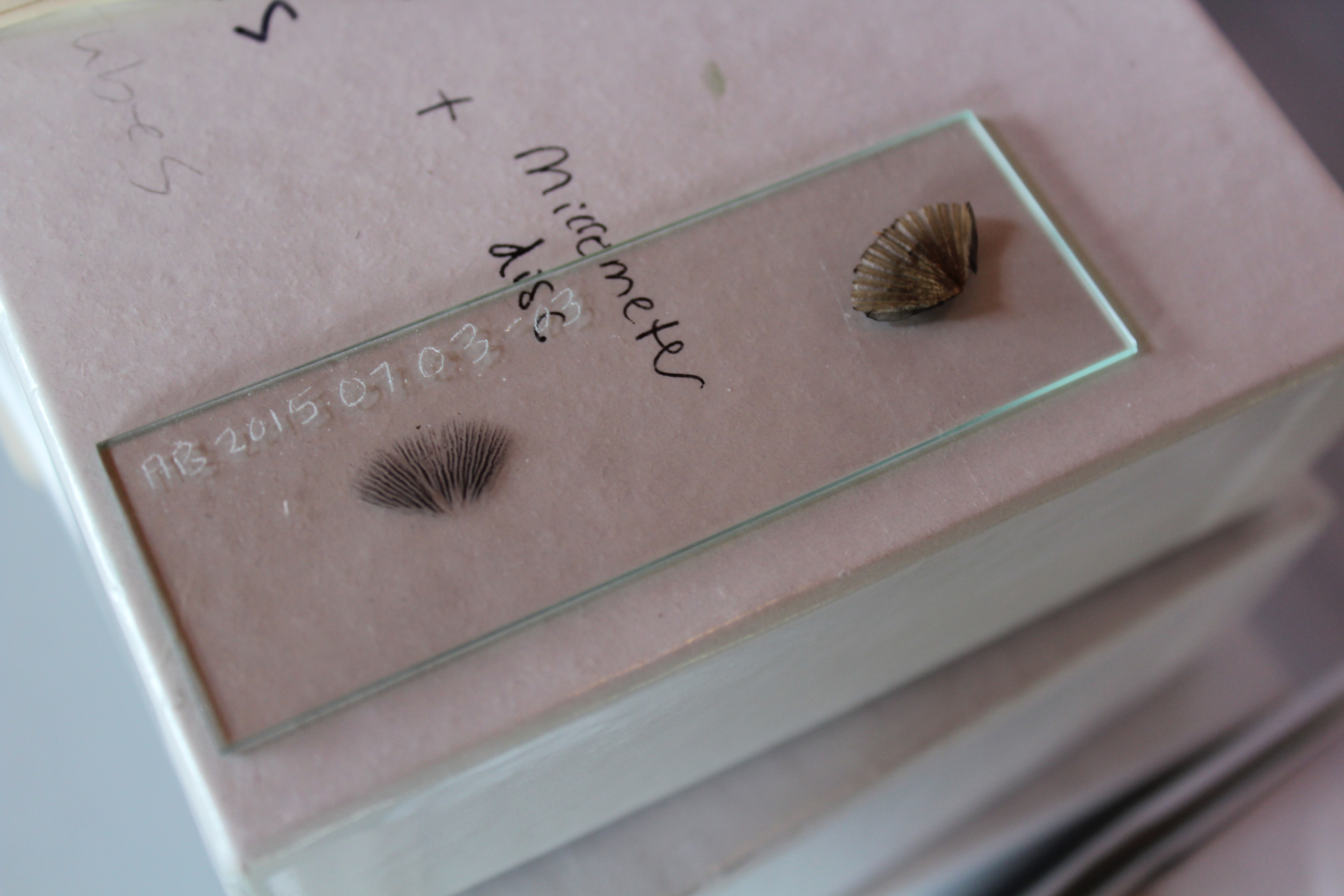

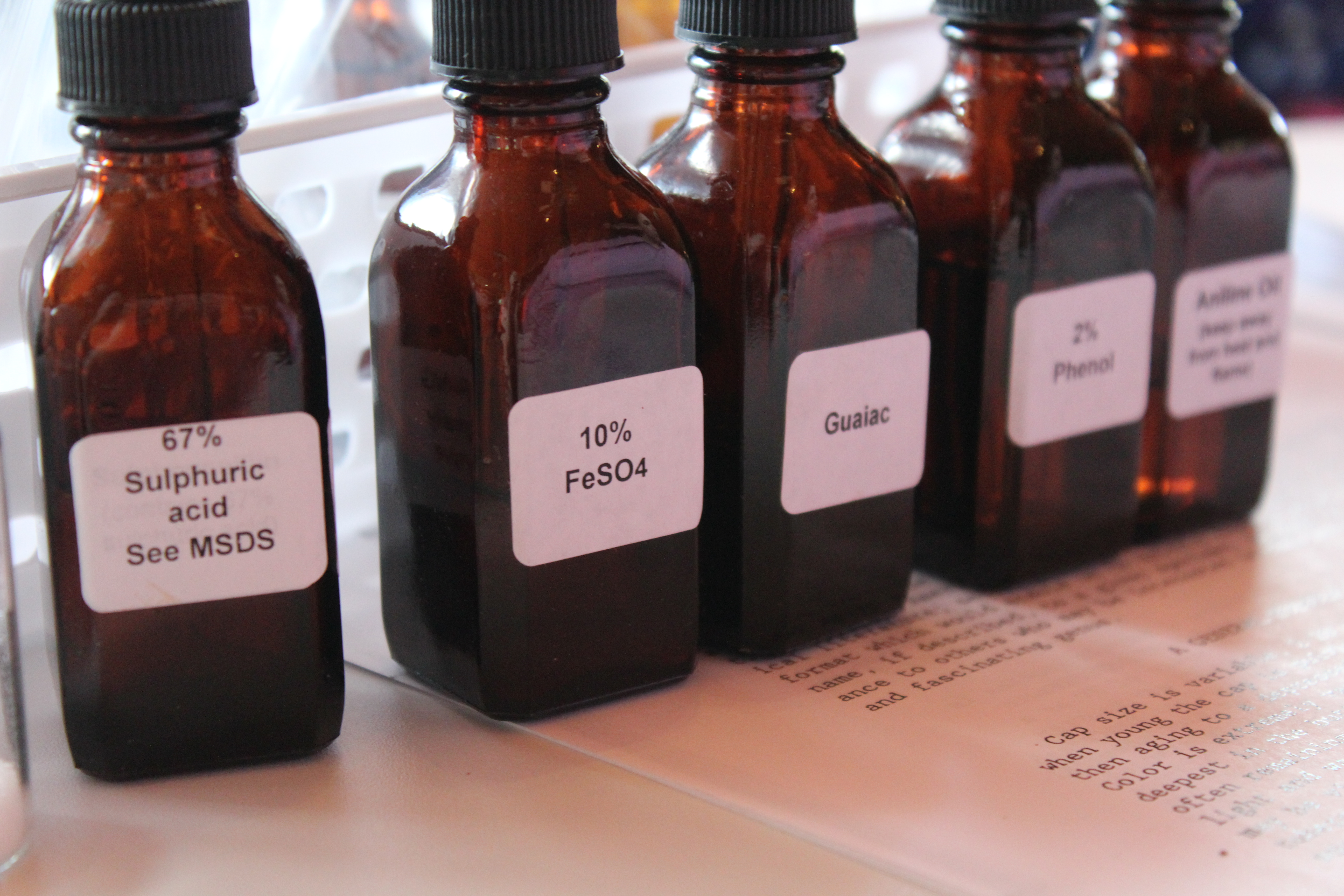

Chemicals can also be used to determine the species of a mushroom. One by one, the above chemicals were added to small pieces of the Russula in a well plate. Each of the chemicals made some species of mushrooms turn colour, while other species remained unchanged. Depending on which chemicals make the Russula turn colour, the species of the mushroom can be narrowed down.

It is evident that, one piece of Russula has begun to turn red, while another has turned a dark green and a third is beginning to turn a deep brown. This helps narrow down the groups of species to which the Russula could belong. Unfortunately, though, these results didn’t reveal the exact species of the mushroom.

Finally, mushrooms were placed in a drying rack overnight for preservation in the NBM Collections and Research Centre. Pictured above is a mushroom of the genus Cantharellus after a night in the drying rack, ready to be added to the NBM Herbarium!

Comment(1)

Dr. Rodham E. Tulloss says:

October 6, 2016 at 6:22 pmHello, Amanda. This is Rod Tulloss from the Campobello foray. I have received the dried specimens that you mailed. Thank you very much. I would like to have your email address so that I could communicate with you further. – Rod