King of the Fleet – the Sequel (Conservator’s Perspective)

Dee Stubbs-Lee, NBM Conservator

In 2017, I received a message that the Humanities Department was considering the acquisition of a shadow box ship model for the NBM collections. There was a passing mention that “perhaps it needed a little bit of conservation attention” and I was asked to review it to see what was possible. Intrigued, I asked for it to be brought to the conservation lab for examination. A short time later, the shadow box arrived and I could see immediately that it would be quite a challenge. However, as I say, “Almost nothing is beyond conservation treatment – some things will just take a little longer than others!”

What arrived in the lab was a shadow box containing dozens of pieces of (what used to be) a ship model. Most of the sails were dislodged from their rigging lines and were laying on the “ocean” or dangling precariously. Masts were broken and there were bits of paper and metal scattered about. It also had many years of accumulated dirt throughout both inside and outside.

The first task in any conservation treatment is to thoroughly assess the artifact and write a formal condition report and treatment proposal. This artifact was a bit like one of those 3-D jigsaw puzzles, only without a picture on the box lid. It seemed that there might be a number of missing pieces, and some of the remaining pieces were extremely fragile and crumbled at the lightest touch. The treatment would obviously be time-consuming and challenging.

In order to assess the condition and to figure out how best to proceed with the treatment, access to the interior was essential. The first step was to remove the glass front. The shadow box was positioned on its back and using suction cups, the old, brittle glass was slowly and gently eased out through a slot at the front of the frame.

Once access was gained, the loose pieces inside the shadow box were taken out, documented, and set to the side. It became apparent on closer examination, that the ship model had been previously broken and repaired more than once. Some of the white paint on the front of the wooden sails had splashed over onto some parts of the rigging lines which were made of two colours of heavy cotton or linen thread. The paint was also on some of the deadeye pulleys which were made of glass seed beads. Most of the rigging lines were broken and badly tangled, and those that remained were too deteriorated to reliably support the weight of the carved wooden sails, so it was decided to remove and replace all of the original threads. To do this we acquired new upholstery thread that closely matched the colour, thickness and twist of the originals. The new threads are both polyester, which will help to distinguish them as replacement parts in the future, an important consideration in conservation ethics.

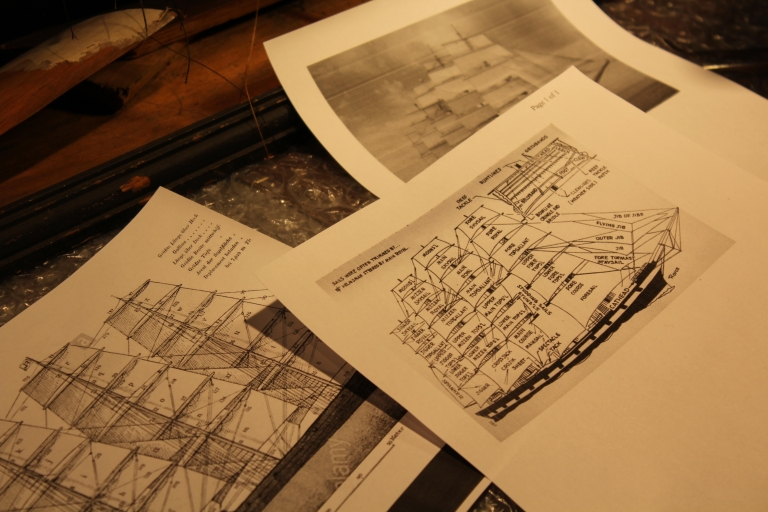

Once all of the parts were revealed, we could see that this was a five-masted barquentine. This is unusual, with two or three masts being far more common. Since most of the model’s original rigging lines were broken and many of the sails were dislodged, extensive research was necessary in order to determine the historically accurate arrangement and attachment points of the sails and rigging. Fortunately, the NBM’s Archives and Research Library Department has a wealth of useful resources on the province’s shipbuilding history.

Every surface of the interior and exterior of the shadow box, the ship model, and the chip carved “ocean” were meticulously cleaned of a century’s worth of dust and grime using a specialized conservation vacuum cleaner. Where necessary, an anionic detergent, distilled water and solvents applied by hand-rolled cotton swabs were used. The surface of the “ocean” was loose inside the shadow box, so it too was removed for cleaning and stabilization. Once the ocean was removed, several interesting surprises were found underneath, including some remnants of the paper flags and banners, some of which, which when pieced together, revealed the model’s name, “King of the Fleet”. A sailor figurine, a gun boat, and an anchor, all made of lead, were also found inside the shadow box, more evidence that the artifact had been modified on at least one earlier occasion, as the ship and the gun boat would not have been contemporary with each other. The sailor was also significantly out of scale with the ship, this was likely another later addition. After discussion with the curator, the decision was made to reinstall the gun boat on the ocean, but to keep the sailor separate from the shadow box assemblage.

In the summer of 2021, Emma Griffiths, a Queens University Master of Art Conservation graduate student, completed an internship at the NBM conservation lab. She took on the daunting task of replacing all of the rigging on the ship model that was then well into treatment.

The final phases of the conservation treatment were completed in the late summer and fall. These included securing the ship model in the shadow box, creating a support structure for the ocean, final surface cleaning, repairing the broken wave crests, securing the gun boat in position, and securing the ocean in place. Next came reattachment of the anchor, re-assembly and restoration of the paper banners, re-installation of the glass front, and in-painting the more distracting chips in the paint on the front frame of the shadow box.

The conservation treatment took place over several years, as the work was undertaken between more time-sensitive projects. In all, it involved hundreds of hours of research and conservation treatment. As much as possible, the original materials were retained. The only new additions were the replacement rigging lines, a few glass beads to replace “deadeyes” that had broken, and a Japanese paper lining, infill, and in-painting to restore the paper banners. In addition, each step of the treatment process was carefully documented and photographed – over 150 photographs in all. Ultimately, the final result is that we now have a much better understanding of the artifact and its condition history. It is safer and more stable and is now much more accessible for future research, exhibition and interpretation potential.

*****************************

Relaunching Samuel William Hopey’s “King of the Fleet”

Samuel William Hopey (Canadian, 1846 – 1936)

shadow box: King of the Fleet, 1890-1910

painted wood, with cotton, glass beads, metal and glass

53 × 94.5 × 19.5 cm

Gift of David P. Simmons, 2017 (2017.36)

New Brunswick Museum Collection

Thanks to the generosity of a descendant of the maker, an intriguing example of the province’s maritime heritage has been added to the New Brunswick Museum’s collections. The skill of Samuel William Hopey (1846-1936), a master carpenter who worked in shipbuilding along the Fundy coast, brought to life a fictional sailing vessel, King of the Fleet.

The New Brunswick Museum (NBM) carefully adds items to its art and histories collections understanding that they will be preserved in perpetuity for current and future generations. Any artifact considered for addition to the collection must meet a number of thoroughly considered criteria. In this case, the provenance of the shadow box was impeccable…even if, initially, its condition left something to be desired.

The NBM houses one of the most significant and extensive ship portraiture collections of in Canada and one particularly fascinating component is shadow boxes. These shallow dioramas of sailing vessels are usually contained within a box structure that be inserted into a wall alcove or set on a shelf or mantel. Almost without exception, the subject matter is a rigged, half or three-quarter version of a sailing vessel that is surrounded by a painted, or sometimes sculpted, seascape or shore scene. This format became especially popular method during the last half of the 19th and early 20th centuries and is a fascinating variation compared to the other types of ship portraiture: paintings, prints, drawings, photographs or ship models.

The vast majority of shadow boxes might be termed “naïve”, “vernacular” or “folk” art since the makers most often had technical knowledge of sailing vessels but little or no formal art training. Currently, the NBM houses seventeen shadow boxes dating between circa 1850 and 1970 with the majority of them from the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The subject of this shadow box is an imaginary, five-masted barquentine, King of the Fleet. Although some sailing vessels were built with up to seven masts (see the 1901 Thomas Lawson of Braintree, MA), they seem to have been exercises in technical capability rather than practicality. Two items currently in the NBM collection, the four-masted schooner, Adonis (1957.66), and the five-masted ship, Maple Leaf (1973.63), depict vessels with more than the usual two or three masts. Certainly, the increased mast possibilities seems to have captured the imagination of many shadow box builders.

The King of the Fleet’s maker, Samuel William Hopey, was born in St. Martins, NB, on 4 May 1846 to John Hopey and Margaret Godsoe. A marriage bond between him and Catherine Ann McLellan of Shediac, NB, is listed in 1873. He appears in the 1881 Census in Moncton as a corker (caulker) with a wife and three children, John A., Alma and Alexander. Matilda Alberta Hopey, a fourth child was born in Moncton in May 1881. Another child, George Stanley Hopey was born at Turtle Creek, Albert County, in February 1891. The 1891 census lists the Hopey family living in the Parish of Coverdale, Albert County. Frank Hopey, another son, was born there in 1895. In the 1901 Census the family is living in Moncton and Samuel’s occupation is listed as carpenter. By 1911, the family is living in Sunny Brae (now a neighbourhood in Moncton), NB, and they continued to live there until Hopey’s death on 19 February 1936. Family history elated by the donor, indicates that Hopey was a ship’s carpenter and master builder who worked all his life in the shipyards along the Fundy coast from St. Martins to Moncton and the making of ship models and shadow boxes was his hobby. This shadow box was taken to the United States in the early part of the 20th century when his son, George Stanley Hopey (1891-1964), moved to the Boston, Massachusetts, area. The King of the Fleet descended to George Hopey’s grandson, the donor.

The NBM’s small but significant survey collection of shadow boxes is likely one of the most comprehensive in the region and has the potential, by virtue of its charming nature, to engage the public in better understanding and appreciating the province’s rich maritime heritage. To date, there is little evidence that the NBM’s collection of shadow boxes has been the subject of much serious research, publication or exhibition. Only six of the seventeen items have makers ascribed or attributed to them. A detailed examination of their characteristics must be undertaken, including a review of their fabrication techniques, a study of the range of imagery they contain as well as a review of their construction relative to shipbuilding. All these aspects must be explored and considered to understand their place not only within maritime-themed art but also within a social history context.

A serious consideration in whether or not to acquire this item was its condition. Years of exposure to light as well as changes in temperature and humidity had weakened much of the rigging which resulted in a significant collapse of its most fragile elements. Since it was contained behind its original glass though, it was determined that all the parts were most likely still there. It was concluded that despite this condition factor, the King of the Fleet would be an invaluable addition to the collection for comparative research, publication and exhibition. In accepting the item, it was with the recognition that the item could be maintained and monitored in order to prevent any further deterioration and that ultimately, a conservation intervention would be necessary to return it to an approximation of its original state.

Stay tuned for more of the story….

References:

Provincial Archives of New Brunswick (gnb.ca) [Marriage Bonds, 1810-1932 and Vital Statistics from Government Records] (accessed intermittently, 2017-2022)

Samuel William Hopey – Ancestry.com (accessed intermittently, 2017 – 2022)