Andrew Sullivan, Zoology Technician, NBM Department of Natural History

The New Brunswick Museum research collection houses over 11,000 individual wet-preserved amphibians and reptiles stored in jars of 70% ethanol. Wet specimens provide anatomical and biogeographic data and can be a source for many methods of analysis. For example, several species of fungi that cause high mortality in frogs and salamanders have been tracked historically using wet collections of amphibians.

NBM wet-preserved amphibians and reptiles collection

Before going into ethanol, wet specimens are injected and “fixed” in formalin (a diluted form of formaldehyde). The formalin stiffens the animal by cross-linking protein molecules in the cells, creating a rigid scaffold within the animals’ tissues. Unfortunately, this method results in the rapid loss of skin colouration, and because of the protein cross-linking, DNA analysis is usually not possible using current technology.

Fixing frogs

Specimen should be fixed in a way that facilitates standard measurements

Skinning and drying amphibian skins (frogs in particular, salamander anatomy is different and they can’t be easily skinned) has been used rarely in the past to better preserve frog colour patterns. However, as technology has evolved, it is now clear that the method offers new opportunities for both specimen collection and use. In a paper published recently in the scientific journal Herpetological Review, New Brunswick Museum Head of Department of Natural History and Research Curator of Zoology, Dr. Donald McAlpine, and colleague Dr. Frederick Schueler, extended the method to include skinning snakes and borrowed herbarium botanical methods to facilitate the preservation and organization of these skins (see McAlpine, D.F., Schueler, F.W. (2018). Herpetology Meets Botany: Using Herbarium Methods to Archive Dried Skins of Frogs and Snakes. Herpetological Review, 49: 236–238).

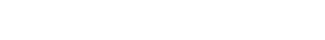

Dr. Frederick Schueler diagram of skinning

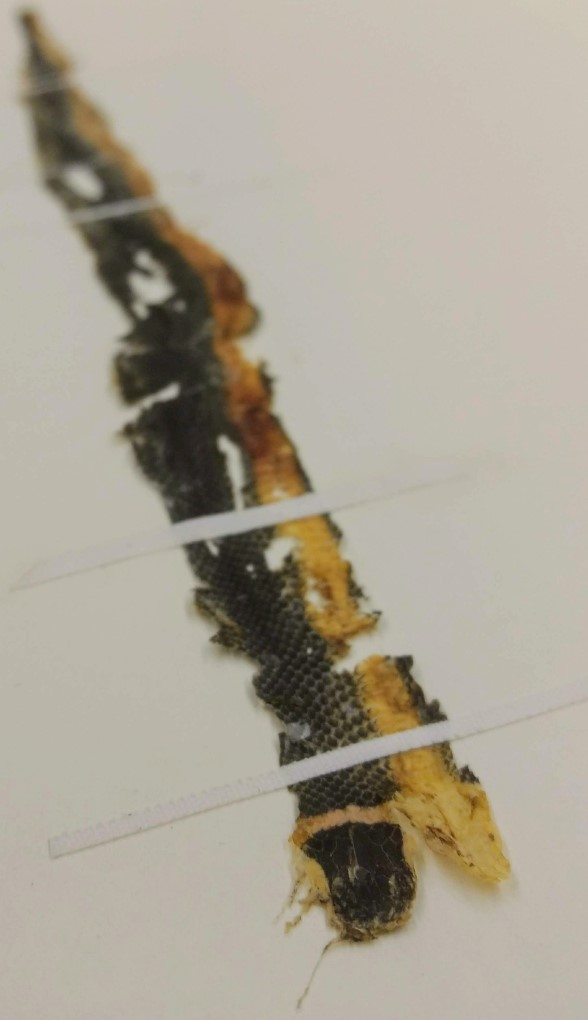

So what do a frog and a flower have in common? Well, both can be dried flat. Frogs are surprisingly easy to skin; the skin is tougher than it looks and is only firmly attached to the body around the hands and feet and over the bones of the head. Ventral incisions are made down the middle of the frog, and along each limb, then the skin is stripped by hand with little need for additional cutting. Snakes are incised down the belly as well, but off-centre along the edge of the vental scales. And of course there are no legs to worry about.

Split frog

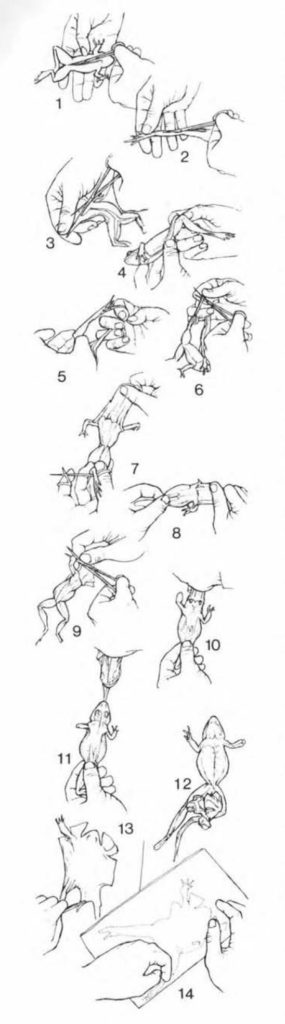

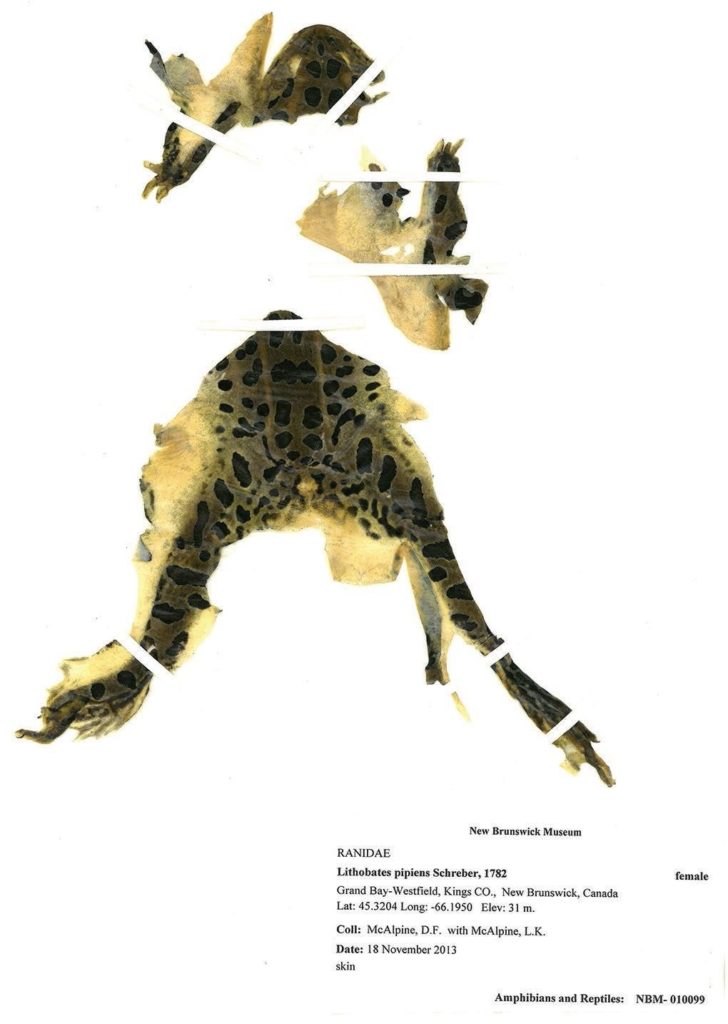

While the immediate outcome seems like a flimsy, crumpled, wad of frog or snake skin,the next step is to spread and flatten the skin. With a blunt tool like a pencap, and some forceps, the skin is pressed and tugged and straightened on a piece of wax paper until nearly all the wrinkles are smoothed and it’s nice and symmetrical – like cartoon roadkill. Another piece of wax paper sandwiches the skin. After that it’s placed in a plant press to dry, or in a pinch, pressed and dried under a rug or even a bed mattress. The final step is to attach the dried skin, now freed from the wax paper, to acid-free, lignin-free herbarium paper using acid-free linen tape.

Wad of skin

Frog on paper

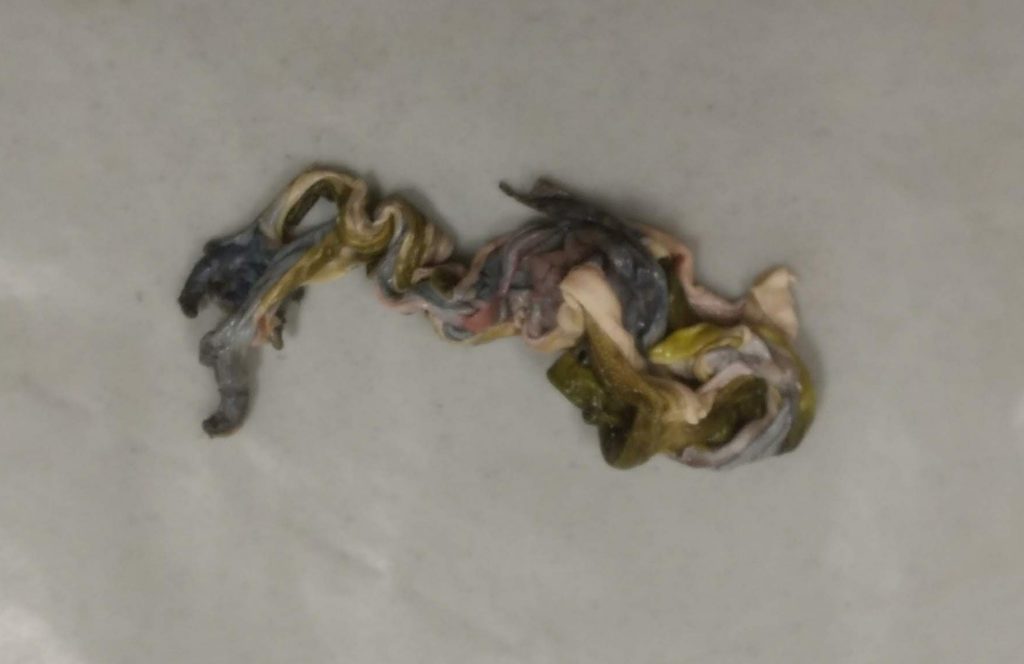

While this preservation method does not result in a natural pose, to say the least, it does have several benefits. Skins can be stored in file-folders in herbarium cabinets, occupying a fraction of the space that is required to store the same number of specimens in jars of alcohol. As with plant specimens, mounted skins can also be easily scanned and shared electronically.

Scanned snake skin

Scanned frog skin

As previousely noted, colours are better preserved in dried skins, and unlike wet specimens, so is DNA! These days, many museums, including the NBM, routinely collect small tissue samples for later DNA analaysis. While these are mainly stored at low temperature (-80o C), separately from other wet or dry specimens. Dried skins stored at room temperature have also proven to be a very useful source of DNA.

Sometimes specimens are not in good enough condition to be preserved whole. The specimen may have been found dead and crushed on a road, or it may be represented only by predator remains. Sometimes snake records are represented by only a cast skin (still a source of DNA). Or a researcher may wish to dissect the fresh specimen or prepare a skeleton. If the bones are of particular interest, skinning allows for the skeleton to be cleaned and the skin saved. Salvaged specimens, such as roadkill, are increasingly important to scientists as permission to actively collect and kill live animals becomes more difficult to secure or species simply become so rare that collecting cannot be justified. Although roadkilled frogs can be in pretty rough shape, the skin can often be saved.

Skeleton

Roadkill snake skin

Scientists have been collecting natural history specimens for hundreds of years, but as technologies and research goals change, so preservation techniques continually adapt. So how many ways to skin a frog? There may be many, but the outcome is always the same – flat.

Video