As New Brunswick’s provincial museum, the New Brunswick Museum not only works with in its own collections but also provides support to other museums across the province. For example, a memento mori— or death memorial—owned by the Musée Acadien de Caraquet was in need of restoration for exhibit at the Musée acadien de l’Université de Moncton. NBM Conservator Dee Stubbs-Lee was able to provide the necessary conservation treatment for the artifact to go on display as part of the upcoming exhibition Always Loved, Never Forgotten: Death and Mourning in Acadia.

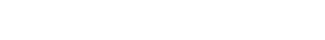

Little is known about the memento mori except that it is in memory of an Anna Duguay, wife of Alf. LeBoutillier, who died on June 8, 1910 at the age of 26. The memorial depicts a graveyard scene with a large wax cross, a smaller cross, and a casket enclosed under a glass dome. Furthermore, the memento mori is embellished with a hairwork garland, which appears to be made using the hair of at least 14 individuals.

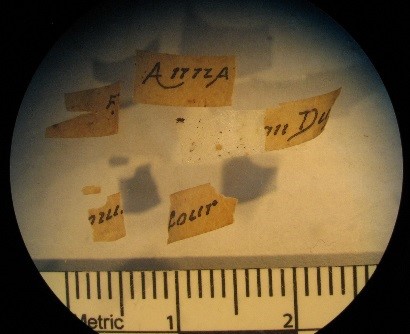

“If you look carefully you can see the hair is not all from one individual: there are a number of different colours and textures of hair,” said Stubbs-Lee. “As I was examining it for my condition report, I noticed that there are a number of little tiny numbered squares of paper. It’s possible each number refers to a different individual.”

Clockwise from top left: the memento mori after treatment without dome; the memento mori after treatment with dome; detail of paper banner providing information on Anna Duguay; detail of hairwork.

Clockwise from top left: the memento mori after treatment without dome; the memento mori after treatment with dome; detail of paper banner providing information on Anna Duguay; detail of hairwork.

The first challenge presented by the memento mori fell to NBM Conservator Claire Titus: transporting the artifact to the NBM Collections and Research Centre in Saint John without damaging it. The memorial was best kept upright with the glass dome in place to provide protection for the wax cross and hairwork. However, the glass itself also had to be protected from breakage and from contacting the artwork inside. Titus thus transported the memento mori in a large Rubbermaid container with acid free cushioning materials in order to absorb vibration caused by movement.

Once the artifact arrived in the Conservation Lab in the NBM Collections and Research Centre, Stubbs-Lee took over the work of the conservation treatment. Various elements of the memento mori were in need of treatment: the glass needed to be cleaned, the textile element washed, the crevices vacuumed of mould and insects, the paper stabilized, and the cracked wax filled and stabilized. All of this had to be done with minimal contact to the fragile hairwork, which was in relatively good condition despite being slightly chewed by insects in some places, but brittle with age.

A treatment proposal was developed and approved by the Musée Acadien de Caraquet before proceeding. First, Stubbs-Lee cleaned the glass dome with vinegar and then used a surgical scalpel to remove hardened dirt. She then dry-cleaned and removed a layer of purple chenille yarn that encircled the graveyard scene. It was extremely dusty and been infested with mould and insects.

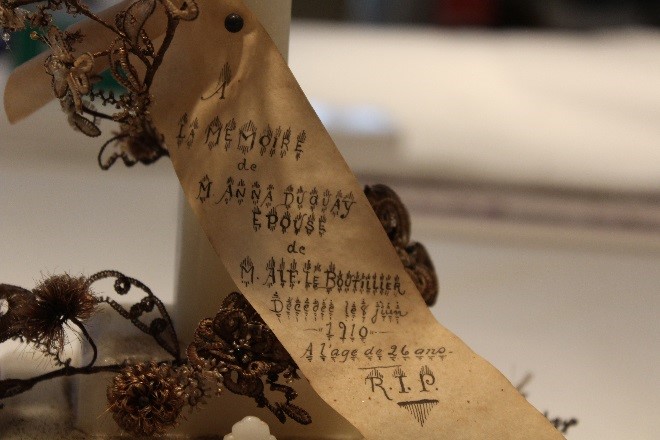

Left to right: NBM Conservator Dee Stubbs-Lee dry-cleans the chenille in the crevasse with vacuum and dental tools; adult carpet beetle carcass and larval casing found during examination and cleaning.

Left to right: NBM Conservator Dee Stubbs-Lee dry-cleans the chenille in the crevasse with vacuum and dental tools; adult carpet beetle carcass and larval casing found during examination and cleaning.

The chenille was then wet cleaned. Before submerging the fabric in water, Stubbs-Lee conducted a spot test with warm distilled water in an eye dropper to make sure that the purple dye would not run. Then it was immersed in a bath of warm distilled water and a mild conservation detergent. Distilled water is used in conservation treatment because it contains fewer impurities, such as metal particles, which can damage an artifact over time. After being washed, the chenille was pinned out and dried.

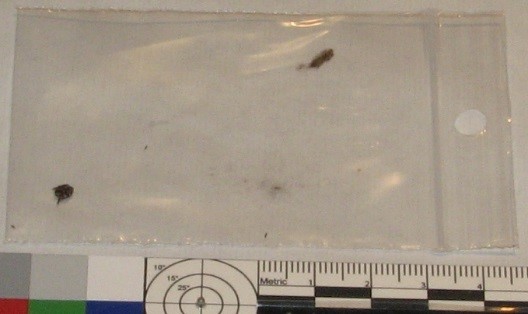

Left to right: the chenille submerged in distilled water and a conservation detergent; the chenille pinned out so that it would not shrink while drying.

Left to right: the chenille submerged in distilled water and a conservation detergent; the chenille pinned out so that it would not shrink while drying.

A number of fragments of paper inscribed with parts of names were found within the artifact. Unfortunately, missing sections and poor condition of the paper meant these could not be restored, but they were carefully documented and retained for research.

Photo: inscribed paper fragments being examined under the microscope.

Stubbs-Lee then went about stabilizing cracks in the large wax cross. Some time since its construction, the memento mori had been exposed to extreme fluctuations of temperature: heat, which partially melted the wax, and cold, which likely contributed to the cracking.

“In conservation we try to use materials similar to the original because it reacts the same way to the environment”, said Stubbs-Lee. The exact composition of the original wax was unknown, so one of Stubbs-Lee’s aims was to fill in the cracks with a material that was stable but slightly softer than the original wax. This way, that any future damage would be absorbed by the new materials, not the original artifact.

“Whenever I put a fill in an artwork—in this case the wax—you want to make sure that the adhesive or the material that you put in there is more vulnerable than the original,” she said. “That way, if something is going to let go then it’s going to be the new material, not the original material adjacent to the repair. Stronger adhesives, for example, are not always better.”

Stubbs-Lee used dental tools to fill the primary crack with surgical cotton, a sheet of sterilized cotton manufactured for medical applications, but useful for a variety of applications in the conservation lab. The cotton filling will be easy to remove in future, if necessary.

“One of the guiding ethical principles of conservation work is the idea that everything you do to alter an artifact should be permanently reversible in the future,” she said.

Stubbs-Lee then covered the cotton with a layer of orthodontic wax, gently pressed into place using tweezers. The wax was covered with a layer of silicone covered Mylar (a clear polyester film) and then touched with a warm tacking iron on low heat to make it flow into the crack.

“I had to warm the wax just enough to slightly melt it and have it flow evenly into the area I was filling, being very careful to not also melt the adjacent original wax of the artifact,” she said. “The silicone coated Mylar will not stick to the wax, and creates a totally smooth surface for molding the wax. I then used a variety of small tools and my fingers to shape the wax into the same profile as the original artifact.”

Clockwise from left: Detail showing a large crack in the wax cross before conservation; positioning surgical cotton fill in the large gap; softening wax infill using tacking iron on low setting.

Clockwise from left: Detail showing a large crack in the wax cross before conservation; positioning surgical cotton fill in the large gap; softening wax infill using tacking iron on low setting.

As a final part of conservation treatment, Stubbs-Lee made recommendations for future care and handling of the memento mori, including recommendations about light and temperature.

“A key part of conservation work is the cleaning and repair of pieces. That is an important part of what we do,” she said. “It’s often what attracts conservators to the field — but conservation is really much more holistic than that. A lot of our job is predicting all the factors that put an artifact at risk of damage and figuring out what we can do to make those things less likely to happen.”

The conserved memento mori can be seen at the Musée acadien de l’Université de Moncton from October 7, 2015 to April 17, 2016.