Introduction

The effects of some of the agents of deterioration we will explore in this series.

Have you ever wondered what causes objects to fall apart or deteriorate over time? Whether in museums or in our own homes, the causes are similar. Every day at museums around the world, Conservators combine the arts and the sciences to preserve collections from the many factors that can lead to their deterioration and loss. Conservators describe these factors as the “Agents of Deterioration”. NBM Conservator Dee Stubbs-Lee will help us explore each of these Agents of Deterioration in more detail.

Every object that has ever existed has begun the process of deterioration as soon as it was made. Some of these processes happen quickly and dramatically, others are much more subtle and may take many years to become visible. Condition depends partly on the materials something is made from, and partly is a result of everything the object has experienced over time. An object may be collected by a museum at any point during this deterioration process. Although condition is a consideration in the acquisition of an object, a far more important consideration is what we know about the object and what it can teach us. Sometimes, objects in even very poor visible condition can reveal a great deal of useful information for research. All of the objects we will show you in this series have visible condition issues. They have been carefully chosen as illustrations of what each of the Agents of Deterioration will do, given time and opportunity.

Direct Physical Forces

“NBM 2007.16.1. Wheelchair, Canadian, 1900-1925. The woven cane seat had been damaged by pressure from above. This artifact underwent extensive conservation treatment to repair this old damage in preparation for the NBM’s 2018-19 feature exhibition, Legacy of Victory: New Brunswick in the Wake of the First World War. Left, before treatment; right after treatment.”

“NBM 1966.88.1. New Brunswick rocking chair c. 1850. The stretcher and rockers are well worn with use. In the museum context, attempting a repair is not appropriate because this shows significant evidence of historic use.”

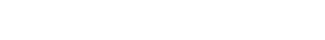

“NBM A66.4 F. Gilded picture frame c. 1870. The gilding, or gold leaf, has been extensively worn off the horizontal surfaces. This is common on historic gilt frames and is often the result of years of overly aggressive dusting. The dark areas you see are not dirt, but exposed bole, or ground layer, where the gold leaf has been completely worn away.”

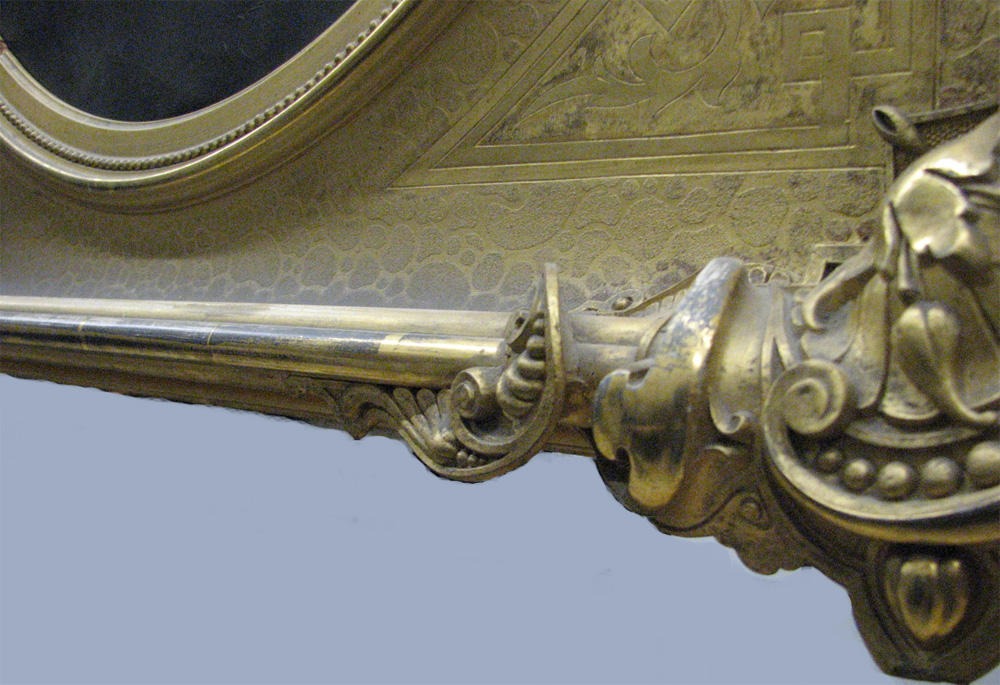

“NBM A65.23. Earthenware dish, English c. 1780. This cracked ceramic dish has a very old repair with a metal staple. This was how valuable ceramic pieces were repaired in years past, before reliable adhesives were developed. The old repair itself is now of curatorial interest as part of the history of the artifact and so we would not choose to remove it.”

Direct physical forces can be quick and dramatic, such as when a dish slips out of your hands and shatters on impact when it hits the floor. It can be slow such as when an object distorts due to the effects on gravity acting on it over many years. It also results from daily wear and tear when an object is used. Such wear and tear is considered evidence of historic use, and can actually be a useful source of important information that helps us to understand an object’s history. The Conservator must balance the goal of preserving the object while also preserving this evidence of use and change.

Thieves, Vandals, and Displacers

“NBM X16623.1-2. Two carved figures attributed to John Rogerson, c. 1860. The figure on the left has been painted at some point in its history. Not all “vandalism” is done with the intent to cause harm. Museum conservators today view such overpainting of an object as inappropriate.”

“NBM 21942. Porcelain plate, late 18th century, Chinese. A unique accession number is carefully and discreetly applied to each artifact and specimen in the collection. Can you spot the accession number on the verso side of this porcelain plate?”

Theft and vandalism are criminal acts and are concerns for all collections. Nearly as problematic are well intended but misguided or inexpert attempts to improve or repair an object or work of art. The result, from a conservation perspective, is almost the same as vandalism. But what is a “displacer”? Museums may have hundreds of thousands or even millions of individual objects in their collections. Museum staff must know the location of each of these at all times or else an object may become “displaced”. The multiple moves of the NB Museum collection over the years due to inadequate facilities have created more than a few unintentional “displacers”. In order to help limit the time and energy needed to resolve these issues, modern museum collection management standards require each and every museum object be assigned an individual tracking or accession number. You may have noticed tiny accession numbers written on an object that you have seen in a museum exhibit. Using this number, information about each and every object in the collection is carefully tracked on a database and continuously updated. That information includes the current physical location of each object, which helps to eliminate the displacement problem.

Fire

“NBM 22705. Porcelain dessert plate, probably English, before 20 June 1877. This plate was blackened by intense heat and soot during the Great Saint John Fire in 1877. It was found packed in a barrel at the remains of a house on Queen Square. In this case, the damage itself is a significant part of the curatorial importance of the artifact, because it is associated with a historic event.”

House fires can result in catastrophic losses. They can happen in museums as well, and are probably the worst fate that can happen to any collection or historic site. The world watched in horror as the National Museum in Brazil burned in 2018 and Notre Dame de Paris burned in 2019. Less well known examples happen regularly around the world. Fires will destroy most materials they touch directly and extensive (though sometimes recoverable) damage results from associated soot and ash deposits, from heat and water, as well as the chemicals used in firefighting efforts.

Water

“NBM 2003.16.86. Pieced silk quilt nine-patch quilt from Rexton, New Brunswick, c. 1850. At some point in its history, this quilt had gotten wet, causing the fabric dyes to transfer.”

“NBM 14598. Painted maple chest c. 1800 which is said to have belonged to Gabriel George Ludlow (1736-1808) first Mayor of Saint John. The top of this chest must have been exposed to moisture for a long period of time, causing the finish to bloom and deteriorate. Perhaps a houseplant lived here for many years.”

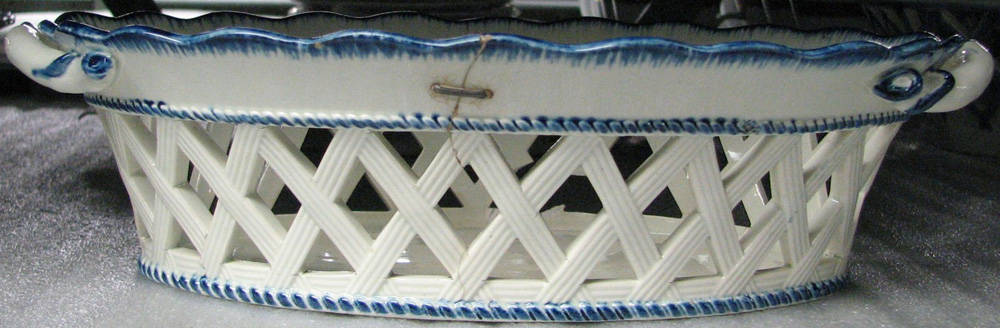

“Couch, c. 1840. At some point in its history, this couch was exposed to a significant amount of water, which has stained and deteriorated the upholstery fabric and caused extensive damage. The dark line around the edge of the stain on the upholstery marks the point where the wetness stopped expanding. Dirt that was dissolved in the water was deposited along this border between the wet and dry areas of the fabric as it dried and the wetness began to recede. Conservators call this dirt deposit a “tide line stain.”

Next to fires, flooding is the single most destructive event that can befall a collection. Flooding can be a result of natural weather events such as rising rivers or heavy rain, or they can be accidental in nature, such as a plumbing incident. In the context of a museum, even something as simple as a slowly dripping pipe can put a collection at significant risk if it is not discovered and addressed immediately. Properly secured and adequate storage facilities combined with constant visual monitoring are effective preventive controls.

Pests

“NBM 1962.93. Chair, Canadian, 1790-1820. The lower part of the chair leg shows insect damage – flight holes chewed by the larvae of wood boring beetles. Chair leg detail on left, chair overall on right.”

“NBM 2003.16.83. Pieced and embroidered silk and cotton Crazy quilt from York County, New Brunswick, 1900-1925. The pink piece has most likely been damaged by insects feeding and leaving behind irregular shaped chewed edges on the remaining fabric. This quilt will also be used as an example in subsequent posts showing other agents of deterioration.. The whole quilt has the same environmental history, but different parts are affected in different ways because of the chemical makeup of the materials.”

“NBM 2009.38.63. Hide covered document box c. 1820. The hair is shedding, most likely due to insects having grazed on the hide at the base of the hairs, causing them to break off.”

“NBM 1959.89.5.2. Wolastoquey pouch attributed to Mary Aquin, made of ermine pelt with wool, silk cotton and glass beads, 1884-1888. Insect damage, including grazing, holes and fur loss. Notice how the damage is concentrated in an area that was covered by a beaded flap. Insect larvae feed most actively when they are protected from light. Detail of insect damage above, pouch overall below.”

Pests, such as certain insects and rodents, can do considerable damage to museum objects, particularly to organic materials (those with a plant or animal origin), such as paper, wood, natural fibre textiles, basketry, furs and leather. For this reason, museums must pay close attention to housekeeping, limit where food and drinks can be consumed, and monitor all collections areas regularly to watch for and record any evidence of infestation.

Contaminants

“NBM 1962.134. Mahogany chair, English, 1780-1820. Splatter marks on the chair legs were probably due to cleaning floors with a wet mop. This has caused accretions on the wood and, over time, caused green corrosion and pitting on the brass. Chair leg detail on left, chair overall on right.”

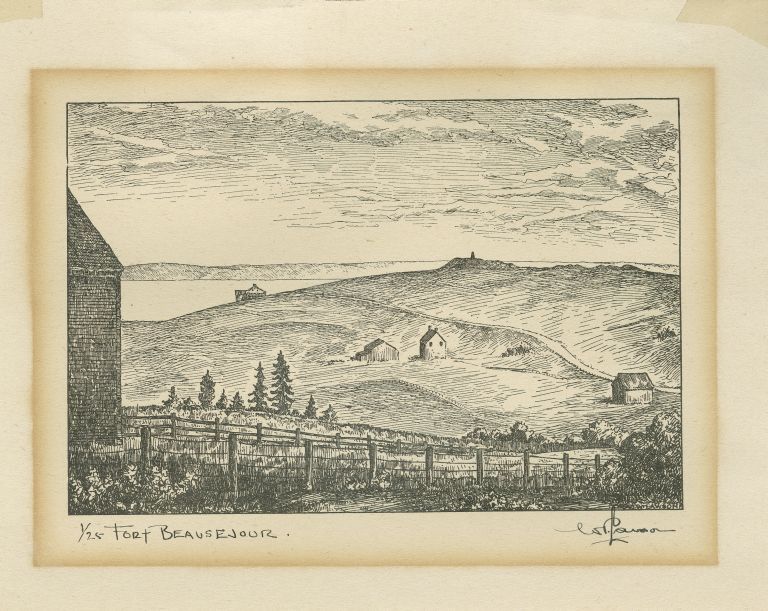

“NBM W319. Etching on wove paper of Fort Beausejour, Canadian, before 1939. At some point in its history, this artwork was in prolonged contact with a standard window matt. Most matt boards are made of wood pulp, which is naturally acidic. Over time, acidic vapors were released from the cut edge of the matt and absorbed into the paper of the artwork itself, resulting in the unsightly brown stain around the perimeter of the image. This phenomenon is known as “acid matt burn”. Window matts made of 100% cotton rag board, though more expensive, are a better choice because they are acid-free and will not cause this kind of damage.”

Contaminants are any foreign material that we don’t want to come into contact with an artifact. Contaminants can come from many sources including dust and dirt, particulates in air pollution, oils from our fingerprints, acids from poor quality packing or framing materials, and residues from cleaning products. Different contaminants affect different materials differently. Contaminants cause metal objects to corrode, can hold moisture against a surface that in turn promotes mold growth, and even simple dust can be an attractant to damaging pests. Very often, contaminants cause slow and steady deterioration over long periods of time.

Inherent Vice

“Private collection. A cellulose nitrate talcum powder box lid showing deterioration beginning at the sharp edges. Early plastics such as cellulose nitrate, which was often made to imitate expensive natural materials like ivory and tortoiseshell, are inherently unstable and will eventually deteriorate on their own due to their chemical composition.”

“NBM 2003.16.83. Pieced and embroidered silk and cotton Crazy quilt from York County, New Brunswick, 1900-1925. Certain specific colours within the plaid patterned fabric, have deteriorated due to chemical incompatibility between the dyes or the mordants and the fibres of the textile itself. Notice how adjoining fabrics in other colours on the same quilt are visually unaffected. We can tell this is due specifically to the inherent vice of the chemistry of this one fabric because the entire quilt would have been subject to the same Agents of Deterioration over time.”

Last time, we discussed the effects of contaminants on artifacts. Sometimes contaminants are not materials from outside, but are chemicals coming from within the artifact itself. In some cases, because of the materials an object is made from, or the way it was manufactured, the object is inherently chemically unstable. Conservators call these situations “inherent vice”, and such cases are among the most challenging preservation problems that Conservators must deal with.

Radiation

“NBM 1965.39. Mahogany and mahogany veneer pot cupboard, probably British, 1800-1815. Belonged to Captain Allen Otty (1784-1859) and his wife Elizabeth (Eliza) Crookshank Otty (1798-1852) of Darlings Island, New Brunswick. Notice how the areas of this piece furniture that faced a sunny window for many years have bleached to a pale yellow brown, while the areas that were not exposed to direct sunlight retain their original rich red-brown colour.”

“ED2007.8. Dress bodice, c. 1900. Silk fabrics manufactured in the nineteenth century were sometimes “weighted” with metallic salts in order to give them better “drape” and other handling properties that were desirable for dressmaking. Unfortunately this chemical processing makes the naturally light sensitive silk fibers even more vulnerable to damage from light as they age. Exposure to light has catalyzed the deterioration and resulted in almost total loss of the weft threads resulting in a dramatic, shredded appearance.”

“NBM 12516.1. Smith’s Celestial Globe, English, c. 1850. This globe is made of paper and plaster, with a varnish layer on top that would have been intended to protect the paper. Over many years, exposure to light has caused the varnish to become irreversibly yellowed and darkened.”

The most familiar form of radiation is light, both visible and ultraviolet, which is a higher energy form of light just beyond the visible spectrum. Ultraviolet, or UV, is not necessary in order for us to see colour, so museum lighting and framing materials are generally designed to eliminate or filter out the UV. All light damages objects on a molecular level, causing organic materials to physically break down, and colours to fade or change. Damage from light exposure is cumulative (it adds up over time) and irreversible. For this reason, museum objects that are particularly sensitive to light must be exhibited only under low light levels and for very limited periods of time, and when not on exhibit are stored in complete darkness in order to slow this deterioration as much as possible.

Incorrect Temperature

“OB 74.1358. Seymour Family memorial wreath, 1875-1876. You may remember our series detailing the extensive conservation treatment of this object carried out at the NBM conservation lab in 2019 in support of our provincial partner, THC Heritage Branch, and the Bonar Law Common heritage site in Rexton, New Brunswick. Many of the wax flowers (like the one shown in this detail) had melted into the dried moss backing, deforming and exposing the paper support inside the flower. Wax has a relatively low melting point so it is easily damaged by an environment that is too warm. Melted wax flower detail on right, object overall on left.

Preservation of museum objects requires that they be stored and exhibited within stringent environmental controls. Heat catalyzes the chemical reactions that are responsible for all forms of deterioration. Cooler conditions are better for the preservation of most materials, and particularly sensitive materials such as early plastics and some biological specimens are actually stored at the museum frozen. Freezing is also a routine part of our pest control measures when materials come in to the museum. We have to be especially careful in handling them during this process, though, as many materials become very brittle when frozen. Even worse than conditions that are either too warm or too cold, are conditions that fluctuate dramatically over short periods of time resulting in unintentional physical damage.

Incorrect Relative Humidity

“Late 19th century work table made of mahogany, basswood, and cedar. The veneer layer has cracked and bubbled on one end. This was probably caused by different rates of expansion and contraction in the different wood species due to fluctuating relative humidity (RH) levels.”

“NBM 2005.16.24. Mahogany and birch veneer table, Canadian, 1790-1800 from the Pickett Family, Kingston and Oak Point, New Brunswick. Marquetry inlay can come loose and pop off when environmental conditions fluctuate. Changes in relative humidity can cause the wood to expand and contract and cause the animal hide glues holding the inlaid pieces in place to become brittle and lose their adhesion.”

Last time, we discussed the effects of incorrect temperature. A closely related but even bigger problem is the question of incorrect relative humidity. Relative humidity (RH) is a measure of the amount of moisture in a volume of air relative to how much moisture that air can hold at any given temperature, expressed as a percentage. The two are inversely proportional: when temperature goes up, relative humidity goes down and vice versa. Conditions that are too damp can cause insects to breed, mold to grow, metals to corrode, soluble dyes, inks and paints to run, and paper to curl. Conditions that are too dry lead to physical breakage as materials become more brittle. As with temperature, fluctuating levels of RH are even more problematic than steady but less than ideal levels. All materials expand and contract to some degree with changes in these environmental conditions which can lead to damage and deterioration.